What’s a Strength Assessment for Runners Like?

Five common tests in the runner's strength assessment battery.

Welcome to the third instalment in our strength assessment series.

I previously wrote about:

In this article, I cover strength assessments for runners.

Specifically, I elaborate on five test examples and their relevance to running.

Isometric mid-thigh pull

Run specific knee/ankle/hip isometric tests

Hip abduction/adduction isometric test

Hop test

Single-leg balance test

At the end of the article, I share a vlog by professional British marathoner Phily Bowden. She shares how she is using these assessments to recover from her injury and bounce back stronger.

Strength Assessment Equipment

Before we start, a quick disclaimer:

The article contains demonstrations from assessment equipment manufacturers, VALD, of which I am a user.

However, they are not sponsoring this article, and there are other options in the market to help conduct these tests.

The common theme among manufacturers is that the equipment’s sensors measure precise metrics, e.g. rate of force development to the millisecond, to provide actionable insights.

Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull

The Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull (IMTP) is a multi-joint exercise test designed to assess whole-body strength and force production capabilities.

It requires individuals to pull on a fixed barbell with maximal effort for a short duration (typically 3-5 seconds) while standing on force plates.

The IMTP has many advantages compared to traditional one-rep-max tests, i.e. technical simplicity, safety, better data, less time to conduct, etc.

Peak Force’s Correlation with Maximal Aerobic Speed

Research has found that the IMTP is “a good indicator of running performance,” where it was found to correlate with 2.4km results and maximal aerobic speed (MAS), a critical determinant of endurance performance.

Peak Force Recommendations

Separately, Paul Wilson, DPT has established IMTP recommendations for runners through testing among his clients.

When runners show low total body strength during the rehabilitation of an overuse injury (e.g., Achilles tendinopathy), he focuses on resolving symptoms and building capacity so that the athlete’s maximal strength can be trained once symptoms become more tolerable.

Rate of Force Development’s Correlation With Running Economy

Another metric from the IMTP test, rate of force development (RFD) was also found to exhibit strong negative correlations with oxygen consumption during submaximal running, i.e. running economy.

In recreational male runners, RFD measured at intervals of 0–50 ms to 0–300 ms showed moderate-to-large inverse relationships with running economy at 10 km/h (r = -0.434 to -0.534).

This aligns with the temporal demands of ground contact during running, where force must be applied within 200–350 ms at submaximal speeds.

The finding suggests that runners should focus on ability to rapidly generate force which correspond to the foot contact time (<300 ms).

Hip Abduction/Adduction Isometric Test

The hip abduction/adduction isometric strength test can be performed in many ways using a dynamometer:

Standing or supine

Knee straight or knee bent

Handheld or attached to stationary object

Etc.

Notably, multiple studies have found abductor/adductor strength deficits in injured runners when compared to healthy controls.

For instance, research found runners with Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTSS), commonly known as shin splints, showed 15–20% lower hip adductor peak torque versus controls.

Another study found that runners with Iliotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS) exhibit 7.82–9.82% BWh (body weight × height) hip abductor torque deficits compared to healthy controls, and a 6-week gluteus medius strengthening program increased abductor torque by 34.9% (females) and 51.4% (males), enabling pain-free running.

A systematic review also found strong evidence that individuals with ITBS demonstrate significantly lower hip abductor strength compared to healthy controls.

While there has been no established strength baselines for runners’ adductor/abductor,

Paul Wilson, DPT, recommends a 125N hip abduction benchmark

Extrapolated research data supports recommendations for male runners adductor isometric squeeze >31% bodyweight and for females >22% bodyweight

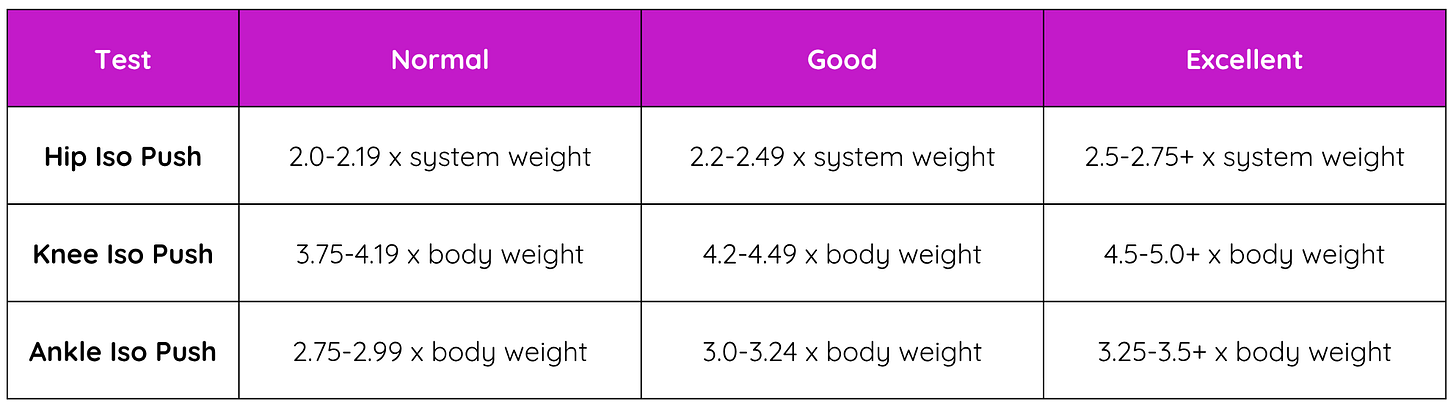

Run-Specific Knee/Ankle/Hip Isometric Test

Isometric training produces the greatest strength gains at the specific training angle.

With this knowledge, Alex Natera, PhD, developed a series of isometric testing and training programmes specific to runners’ mid stance angles in 2017.

It includes protocols focused on hips, knees, and ankles.

Over the years, better data collection and wider adoption has enable strength baselines to be established via these protocols to help runners stay injury free.

I demonstrate the test protocols in the following video (go straight to 4:43 to see the assessments).

In gist, isometrics are uniquely advantageous for addressing specific weaknesses or sticking points in dynamic movements.

The hip/knee/ankle tests addresses those in running - where maximal loading happens when the foot is in contact with the ground.

Hop Test

The hop test is performed with relatively straight legs, utilising the ankle and calf muscles as the primary means of upward propulsion without requiring the deep squatting motion characteristic of other jumping assessments.

The test protocol involves performing rapid, successive hops with the goal of achieving maximum height while maintaining minimal ground contact time, using only the toes and forefoot for propulsion.

Metrics useful for runners from the hop test includes ground contact time and reactive strength index (ground height divided by ground contact time).

For instance, Paul Wilson, DPT, has found that ground contact time of 180–200ms and RSI of >2.5 to be ideal for runners.

Researchers also found a ~3.7% increase in metabolic cost for every 1% increase in ground contact time imbalance.

Additionally, there is early evidence to support hopping as a return to running test, as acceptable correlation has been found between asymmetry in hopping and running performance.

Lastly, daily hopping exercises have also been found to be effective in improving running economy at high running speeds in amateurs. Thus hop testing can be a feasible complementary in training programs.

Single Leg Balance Test

The single leg balance test typically involves standing on one leg with hands on hips and maintaining balance for as long as possible.

Normative values vary by age, with younger adults typically able to maintain balance for 45+ seconds with eyes open and 15+ seconds with eyes closed.

Clinically, a single-leg balance test is used to test neuro-muscular control, which is defined as the interaction between the nervous and musculo-skeletal systems to produce a desired effect or response to a stimulus.

Poor performance during single leg stance tests have been shown to correlate to excessive heel movements during gait and research demonstrated that the balance assessment can predict specific biomechanical patterns that occur during actual running performance.

Single leg balance tests have also been used by clinicians to collectively assess muscular and ligamentous patency in the foot.

For example, clinicians have added the single leg balance assessment into running gait assessments, comparing results with and without footwear.

Lastly, research also found that none of the relationships between balance test performance and running mechanics were moderated by muscle strength. This suggests that movement quality assessment through balance testing provides independent information about running biomechanics.

On the whole, it can be useful for runners to track their single leg balance performance.

Putting Everything Together

In this following video, Phily Bowden shares about her race setback, how she fared for specific strength tests, and her new training plan.

My team is also putting together videos of local runners going though these tests, and how their result and training recommendations differ.

Subscribe to this newsletter to stay in the loop.

Conclusion

There are more than a thousand strength assessments apart from those mentioned to measure different metrics, movements, and body parts.

If you would like to learn more about such exercises, my team:

conducts isometric train-the-trainer workshops

provides strength testing as a standalone service

utilise strength testing in our personal training service

Please contact us if you would like more information.

References

Balachandar, V., Hampton, M., Riaz, O., & Woods, S. (2019). Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis to evaluate lower-limb biomechanics and conservative treatment. Muscles Ligaments and Tendons Journal, 09(01), 181. https://doi.org/10.32098/mltj.02.2019.05

Engeroff, T., Kalo, K., Merrifield, R., Groneberg, D., & Wilke, J. (2023). Progressive daily hopping exercise improves running economy in amateur runners: a randomized and controlled trial. Scientific Reports, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30798-3

Hip Abductor Weakness in Distance Runners with Iliotibial. . . : Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. (n.d.). LWW. https://journals.lww.com/cjsportsmed/abstract/2000/07000/hip_abductor_weakness_in_distance_runners_with.4.aspx

Ho, M. T., & Tan, J. C. (2022). The association between foot posture, single leg balance and running biomechanics of the foot. The Foot, 53, 101946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foot.2022.101946

International Journal of Advanced Research. (2020, June 5). Article detail - International Journal of Advanced Research. https://www.journalijar.com/article/25320/hip-muscles-torque-in-runners-with-medial-tibial-stress-syndrome/

Joubert, D. P., Guerra, N. A., Jones, E. J., Knowles, E. G., & Piper, A. D. (2020). Ground contact time imbalances strongly related to impaired running economy. International Journal of Exercise Science, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.70252/dbrf4451

Lanza, M. B., Balshaw, T. G., & Folland, J. P. (2019). Is the joint-angle specificity of isometric resistance training real? And if so, does it have a neural basis? European Journal of Applied Physiology, 119(11–12), 2465–2476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-019-04229-z

Lum, D., Chua, K., & Aziz, A. R. (2020). Isometric mid-thigh pull force-time characteristics: A good indicator of running performance. Journal of Trainology, 9(2), pp. 54-59.

Mucha, M. D., Caldwell, W., Schlueter, E. L., Walters, C., & Hassen, A. (2016). Hip abductor strength and lower extremity running related injury in distance runners: A systematic review. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20(4), 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2016.09.002

Optimizing Endurance Running Performance and Rehabilitation: A Q&A with Paul Wilson | VALD Health. (2025, April 8). https://valdhealth.com/news/optimizing-endurance-running-performance-and-rehabilitation-a-q-and-a-with

Riera, J., Duclos, N. C., Néri, T., & Rambaud, A. J. (2023). Is there any biomechanical justification to use hopping as a return to running test? A cross-sectional study. Physical Therapy in Sport, 61, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2023.03.008

Schreiber, C., & Becker, J. (2020). Performance on the Single-Legged step down and running mechanics. Journal of Athletic Training, 55(12), 1277–1284. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-533-19

Springer, B. A., Marin, R., Cyhan, T., Roberts, H., & Gill, N. W. (2007). Normative Values for the Unipedal Stance Test with Eyes Open and Closed. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 30(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1519/00139143-200704000-00003

Zhang, Q., Nassis, G. P., Chen, S., Shi, Y., & Li, F. (2022). Not Lower-Limb joint strength and stiffness but vertical stiffness and isometric Force-Time characteristics correlate with running economy in recreational male runners. Frontiers in Physiology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.940761